Did drought end the ancient Maya kingdoms?

Why did the ancient Mayan kingdoms, so powerful and vast, fall?

The conventional wisdom is that a horrendous, long-lasting drought threw their agricultural system into crisis, the kingdoms wasting away, their remains now lost beneath impenetrable jungle.

But by piercing that oppressive canopy, teams led by Brandeis anthropologist Charles Golden and his colleague Andrew Scherer of Brown have uncovered new evidence that throws doubt on that simple story.

They found that some of the communities in the Western Maya Lowlands seemed to have had plenty of agricultural resources until the end, and that the region’s three main kingdoms were functioning very differently — signs suggesting a civilization-wide drought may not explain the collapse of the Maya.

“The Maya are often viewed as a cautionary tale about climate change — this great civilization collapses simply because of a drought,” Golden said.

“Well, that’s not quite what happens. They probably didn’t collapse because of a drought. And even if drought were a significant problem, everybody was facing that climate change differently.”

“The Maya are often viewed as a cautionary tale about climate change — this great civilization collapses simply because of a drought. Well, that’s not quite what happens.”

Charles golden

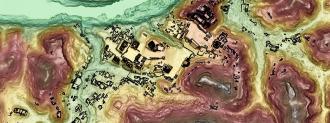

Revelations from on high: To unravel the mystery, the researchers turned to LiDAR, the laser scanning technology that police use to nab speeders, which has recently revolutionized archeology. LiDAR bounces lasers off surfaces and calculates how long they take to return to the source.

Armed with that information, LiDAR scanners can construct 3D images.

When attached to an aircraft, like it was for Golden and Scherer’s research, LiDAR can create a detailed topographical map of a vast area.

“Before, we had these intense portraits of a few places. Now, because we were able to pull back and see this landscape, we can see the whole picture,” Golden said.

That’s useful in and of itself, but what LiDAR removes from the picture is what’s really sparked a research renaissance in Central America: the scans can be adjusted to wipe away the thick canopy of jungle vegetation.

That overgrowth has hidden away more of the Maya and other ancient civilizations than we ever knew — including bogglingly large structures.

Three Kingdoms: The researchers investigated three different valleys in the region, each home to an ancient Maya kingdom’s capital; today, we know them as Lacanja Tzeltal, La Mar, and Piedras Negras.

While the regions have been explored before, their harsh terrain has made unlocking their secrets difficult.

The new study, published in Remote Sensing, blanketed 20 square miles with LiDAR, rescuing over 5,000 structures from the clutches of nature and time — many previously undiscovered.

Aerial scans revealed that the largest city explored, Piedras Negras, did not have any agricultural infrastructure nearby — a sign that people weren’t fearing starvation, they write in the study. The telltale signs of Maya agriculture, like drainage channels and terraced hills, dotted the landscape around La Mar, however — possible evidence of a determined push to grow more food.

“What all that infrastructure suggests is that people in the countryside in this area were investing their efforts to grow more than enough food to feed themselves,” Golden said.

Farming, trade, and war: The infrastructure being found in all three valleys leads the team to believe that the “study region did not experience resource stress” during the time we consider the end of Maya power, they wrote in their study.

The lack of agricultural infrastructure around Piedras Negras suggests that the food grown in the smaller communities of the valleys were being brought to city markets for trade, and that city residents — much like today — were focused on activities other than farming.

Signs of agriculture in all three valleys suggest the region was not facing a food crisis, complicating our theories of how the ancient Maya kingdoms ended.

And with all of the hilltop forts they found strewn over the landscape, said activities may have included war with their neighboring kingdoms. All of it complicates the commonly accepted narrative of a civilization brought low by a fluke of climate change, and reveals the diversity of how the Maya lived in different regions. Cities in Belize can be ringed by terraced fields, while the Yucatan is piled with agricultural landscapes, nary a metropolis in sight.

“What we see is a story about variability,” Golden said. “The communities in this area were working and dealing with the challenges of drought, of warfare, of bad kings and good kings in very different ways. It shakes up our picture of who the Maya were.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].