On May 20, President Donald Trump announced the Golden Dome Missile Defense Shield, conjuring an image of a flawless defense system that could knock down every missile aimed at the United States from any direction.

“Once fully constructed, the Golden Dome will be capable of intercepting missiles even if they are launched from other sides of the world, and even if they are launched from space… hypersonic missiles, ballistic missiles, and advanced cruise missiles — all of them will be knocked out of the air,” Trump told reporters, adding that the system will be fully operational before the end of his presidential term.

This is an inspiring but unattainable vision. However, the headline-grabbing Golden Dome proposal can serve as the spark for a more realistic homeland defense upgrade, one built on proven hardware and continuous improvement, rather than on promises of instant perfection.

Completing Reagan’s dream

Trump noted during his announcement that the Golden Dome will “truly be completing the job that President Reagan started 40 years ago,” so it’s worth taking a look back at what sort of foundation the US already has in place for the newly proposed missile defense system.

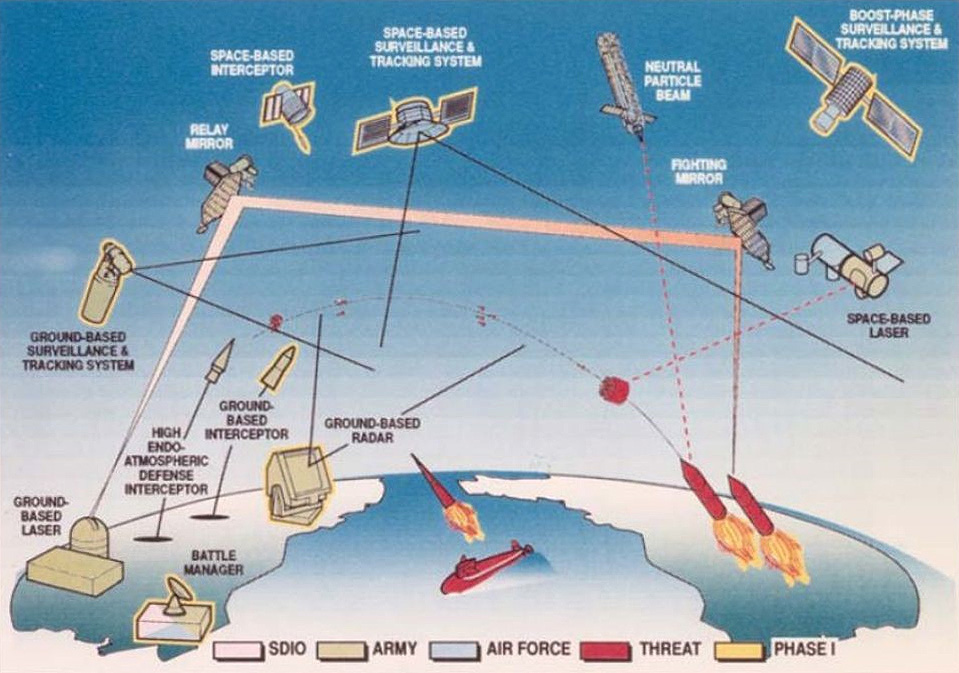

In 1983, during the final stages of the Cold War, President Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a plan to build a defense system capable of intercepting and destroying enemy missiles before they reached US territory. Because the proposal included space-based missile systems, it was soon nicknamed the “Star Wars” program.

In 1986, the US invited Israel to participate in the SDI, a move driven by growing concerns over the proliferation of long-range surface-to-surface missiles in the hands of hostile Arab states. On May 6, 1986, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the two countries, outlining joint development efforts. It was later agreed that Israel would focus on an anti-ballistic missile system tailored to its regional threats, with the US covering 65% of development costs.

On June 29, 1988, Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin signed an official agreement with the US to develop what would become Arrow, a pioneering ground-launched missile defense system jointly developed to intercept and destroy long-range ballistic missiles, and later adapted to intercept threats above Earth’s atmosphere. At the same time, the US began developing similar systems, including the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) and a version of the Patriot system modified for missile interception.

Like other ambitious military and space projects during the Cold War, including the Skylab space station, the SDI was based more on vision than on existing capabilities. Critics argued that the program was unfeasible and prohibitively expensive. Ultimately, the Clinton administration shelved it following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The closest thing the SDI had produced to a space-based missile defense system, the Brilliant Pebbles program, was cancelled two years later without ever making it to tests in space.

The unfinished SDI cost the US more than $25 billion, but it is considered to have played a major role in the eventual US victory in the Cold War by pressuring the Soviet Union into unsustainable military spending that accelerated its economic collapse.

Modern missile defense

With the Cold War over, the US refocused its missile-defense initiatives from protecting the homeland to shielding forces deployed in the Middle East. Israel, meanwhile, concentrated on protecting its civilians and military bases from regional missile arsenals by building a layered defensive shield to detect and intercept weapons fired at it from various ranges:

- The Iron Dome weapon system for short-range rockets and mortars (ones fired from within 43 miles)

- David’s Sling for medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles (ones fired from 25 to 190 miles away)

- The continually updated Arrow system for high-altitude threats fired from farther away

Trump has pitched the Golden Dome as an “Iron Dome for America,” but with even better technology, including the space-based intercept weapons envisioned by the Reagan administration. “We will have the best system ever built,” he told reporters in May.

But even with a budget of $175 billion, creating the missile defense system Trump envisions by early 2029 is an overly ambitious goal.

Conceptually, a missile defence system program can be distilled into three functional centers: sensors to detect the threat, a command and control center to decide whether to intercept it, and defensive missiles to destroy it. Every layer must work flawlessly and within tight time constraints. Building a national missile shield for the continental US would rank among the most complex engineering feats in modern military history.

A bigger war chest and technological prowess alone will not shorten a learning curve measured in real-world interceptions, failures, and redesigns.

Israel’s recent performance illustrates why. During the June 2025 war with Iran, its Arrow, David’s Sling, and Iron Dome artillery batteries intercepted well over 500 Iranian long-range projectiles with a success rate hovering around 86%. Many of those ballistic missiles originated from a range of about 1,200 miles, comparable to a missile fired from Havana aimed at Chicago.

That level of defensive proficiency was not whipped up in a few procurement cycles. It was forged over decades of iterative design, live combat, and painful lessons from rockets launched by Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Gaza in the years preceding the 2025 war.

The US certainly enjoys deeper pockets and broader technology bases, but Israel is only about the size of New Jersey. The Golden Dome will need to protect an area 475 times larger than the Iron Dome, while facing the same physics, software, and integration hurdles that Israel spent years overcoming.

In other words, a bigger war chest and technological prowess alone will not shorten a learning curve measured in real-world interceptions, failures, and redesigns.

Facing up to that reality is the first step toward building a credible US homeland missile-defense architecture. The second is figuring out how the US could improve its existing missile defense systems over the next four years and then making those upgrades.

For instance, the new Long Range Discrimination Radar in Alaska, which recently tracked a live ICBM target, could be paired with an additional radar on the Atlantic seaboard to cover threats approaching from the east. Aegis destroyers operating offshore or an Aegis Ashore site near New Jersey could provide midcourse intercepts, while THAAD and upgraded Patriot PAC-3 batteries ring the cities to handle terminal-phase shots.

These weapons already plug into the US’s existing Command and Control, Battle Management, and Communications network, meaning a rudimentary “mini-dome” could be assembled through integration, testing, and incremental upgrades, rather than an all-at-once technological leap.

The US can use the coming years to establish the foundation on which a broader Golden Dome must eventually rest.

Such a step would not create the hermetic shield Trump describes, but it would give some US cities and key areas a level of protection they currently lack.

New York City, for example, lies outside the coverage area of America’s existing Ground-Based Midcourse Defense interceptors, which are located at Fort Greely in Alaska and Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. If someone launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) toward the city today, early-warning satellites would likely detect it during some phase of its flight, but the absence of 24/7 interceptor batteries on the East Coast means the missile could not be reliably intercepted in flight.

In contrast, under an enhanced missile defense system, radars positioned along America’s East Coast would pick up the missile’s track, the command center would rapidly determine its threat level, and a Ground-Based Interceptor (GBI) stationed at a northeastern site, like Fort Drum, or an SM-3 missile launched from a naval ship offshore would attempt a midcourse or terminal interception before the missile reached its target.

The US can use the coming years to establish the sensors, interceptors, and command architecture on which any broader Golden Dome must eventually rest. In time, once the foundational elements are in place, the system could naturally expand to include advanced space-based interceptors, offering broader coverage and earlier detection capability.

Worth the investment?

Feasibility isn’t the only issue with Trump’s Golden Dome, though. There’s also the question of whether Washington should pour resources into countering a direct yet statistically low-probability missile strike on the homeland, or channel funds toward cyber-resilience, climate adaptation, and economic competitiveness.

Ultimately, while the threat of an attack on American soil is low, it is not non-existent.

North Korea now fields the solid-fuel Hwasong-18 intercontinental ballistic missile, which it has successfully flight-tested three times since 2023. It has been assessed as able to reach any point in the continental US. Russia has begun deploying the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, designed to maneuver at more than Mach 20 and evade existing defenses.

In April 2024, John Plumb, then-US Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, warned that “the scale and scope of these multi-dimensional threats present significant risks to the American people and the homeland,” underscoring the need for renewed investment in missile defense.

The US faces a dilemma. If it does too little, it risks being caught off guard by what will seem like a surprise attack, even though the threat has been visible for years. If it does too much, it risks spending billions on a defense system that may never be used. But as North Korea, Russia, and China expand and modernize their arsenals, this decision will shape whether the US stays ahead of these threats or falls dangerously behind.

Skeptics once thought an Iron Dome was unnecessary. Waves of rockets and missiles proved them wrong.

Any entity attempting to defeat the US on American soil will ultimately lose, yet history proves that some will still try. Such was the case at Pearl Harbor and on 9/11. America’s enemies sometimes act according to motivations that challenge conventional Western logic. Those who carried out the aforementioned attacks gained nothing but devastating retaliation, yet similar groups remain willing to strike again.

Just as the threat once came from kamikaze pilots and hijacked commercial jets, today’s most pressing danger is from missiles. Skepticism about spending $175 billion on President Trump’s “Golden Dome” echoes the doubts voiced in Israel two decades ago when an Iron Dome and the Arrow program both seemed fanciful and unaffordable. Skeptics didn’t believe that Israel’s enemies would ever follow through on their threats. Eventually, waves of rockets and missiles proved them wrong.

The Iron Dome and the Arrow system demonstrated remarkable effectiveness, intercepting thousands of incoming rockets and significantly reducing casualties and damage to vital infrastructure. Their success validated the earlier investment, preserving lives, boosting national morale, and enabling Israel’s leadership greater flexibility in crisis decision-making.

A layered American shield, even if it is less impenetrable than promised by Trump, would serve the same purpose: buying decision-makers precious minutes, assuring the public that the nation’s political and financial heartlands are not vulnerable, and planting the technological seeds for wider coverage later on.

In that sense, turning the Golden Dome from rhetoric into a disciplined, incremental project is not extravagance. It is a prudent investment in the continued security of the US.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].