Artificial meat is under attack: Several US states, including Montana, Mississippi, and Alabama, have banned it, taking their lead from Florida, which outlawed it in 2024. The irony? One hundred and eighty years ago the Sunshine State would pioneer another artificially produced product that was traditionally harvested from nature: ice.

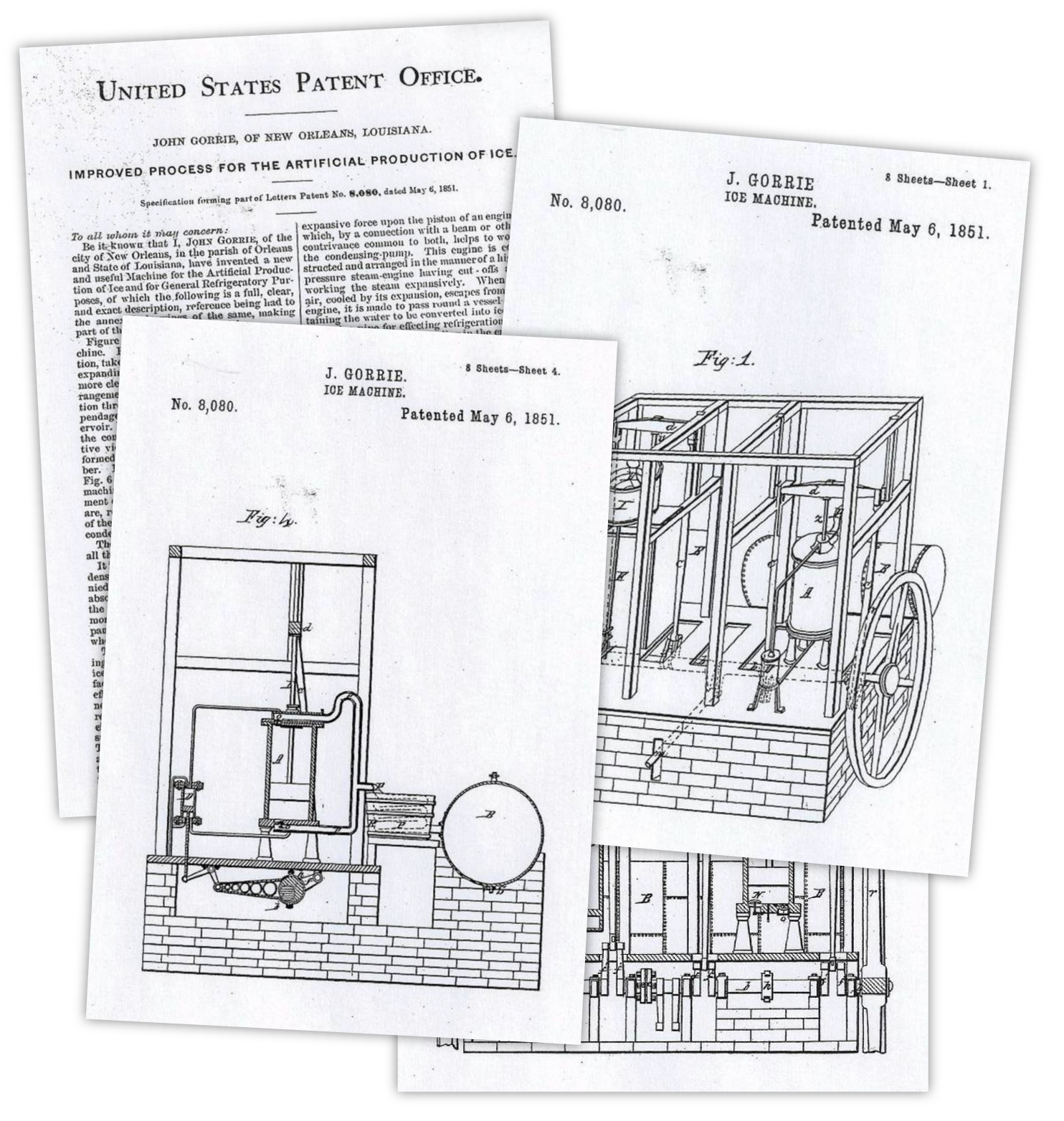

In 1851, physician and Florida resident Dr. John Gorrie was granted a patent for an ice-making process after years of experimenting with artificial cooling methods for medical purposes. This would be the genesis of the modern refrigeration systems we all enjoy today.

The notion of “manufacturing” ice through an industrial process likely felt similarly strange as lab-grown meat feels today — a product of a natural process suddenly produced through scientific wizardry.

In 1847, Gorrie would astonish guests at an event in Florida by serving wine cooled with artificial ice in the middle of summer, when ice was often scarce. Some scoffed at the notion, with The New York Daily Globe reportedly writing that same year: “There is a Dr. Gorrie, a crank, down in Florida, who thinks he can make ice as good as God Almighty.”

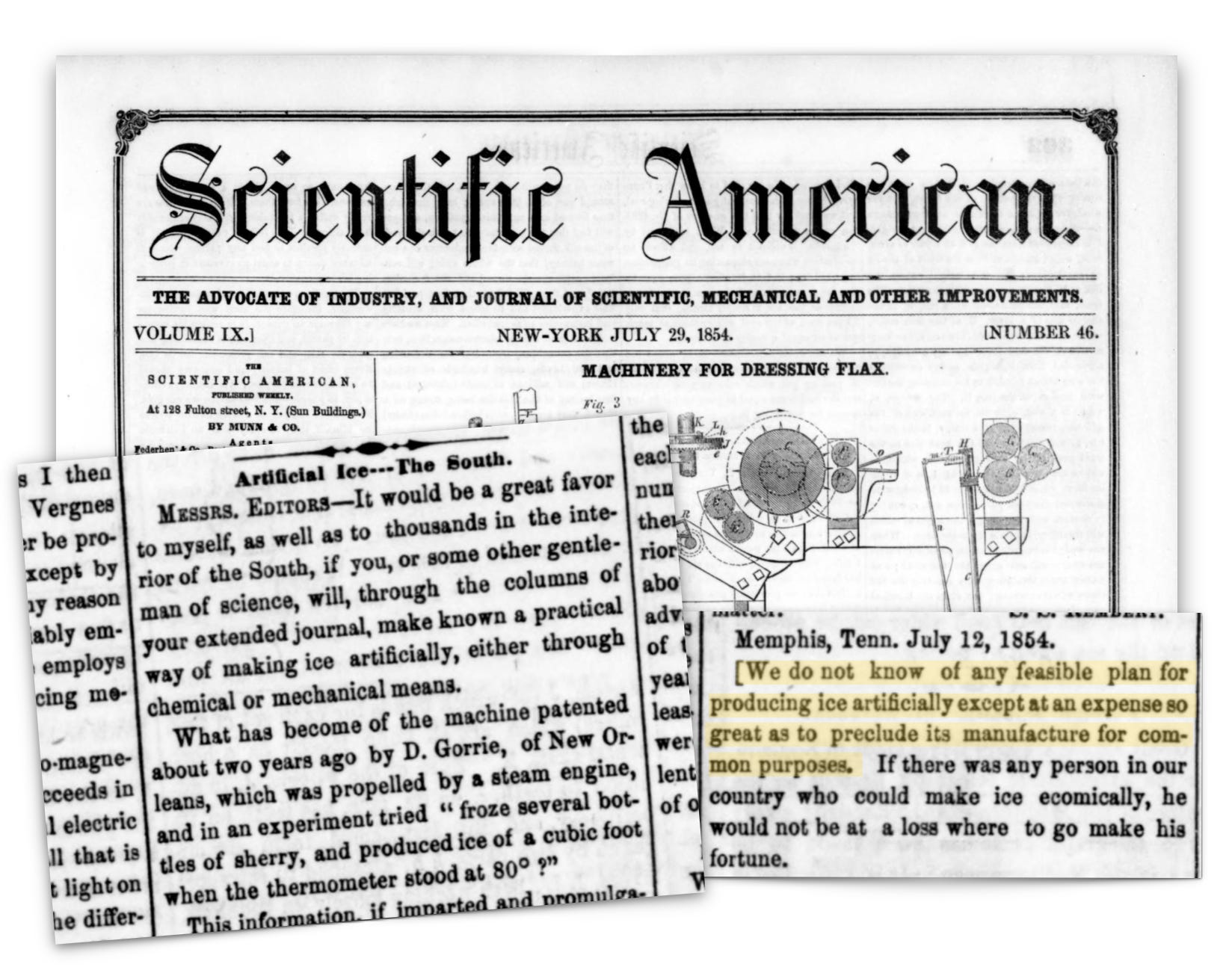

Scientific American would testify to the validity of the method in 1854 in answer to a reader question about it, but noted the process was too expensive to be made in commercial quantities for common purposes — a bit like lab-grown meat today and other early innovations through history.

A year later, Dr. Gorrie would die, and ice would be manufactured in large quantities for the first time. It would be many decades before the price fell enough to compete with the harvested ice industry, but once it did, the incumbent ice industry pushed back.

The backlash

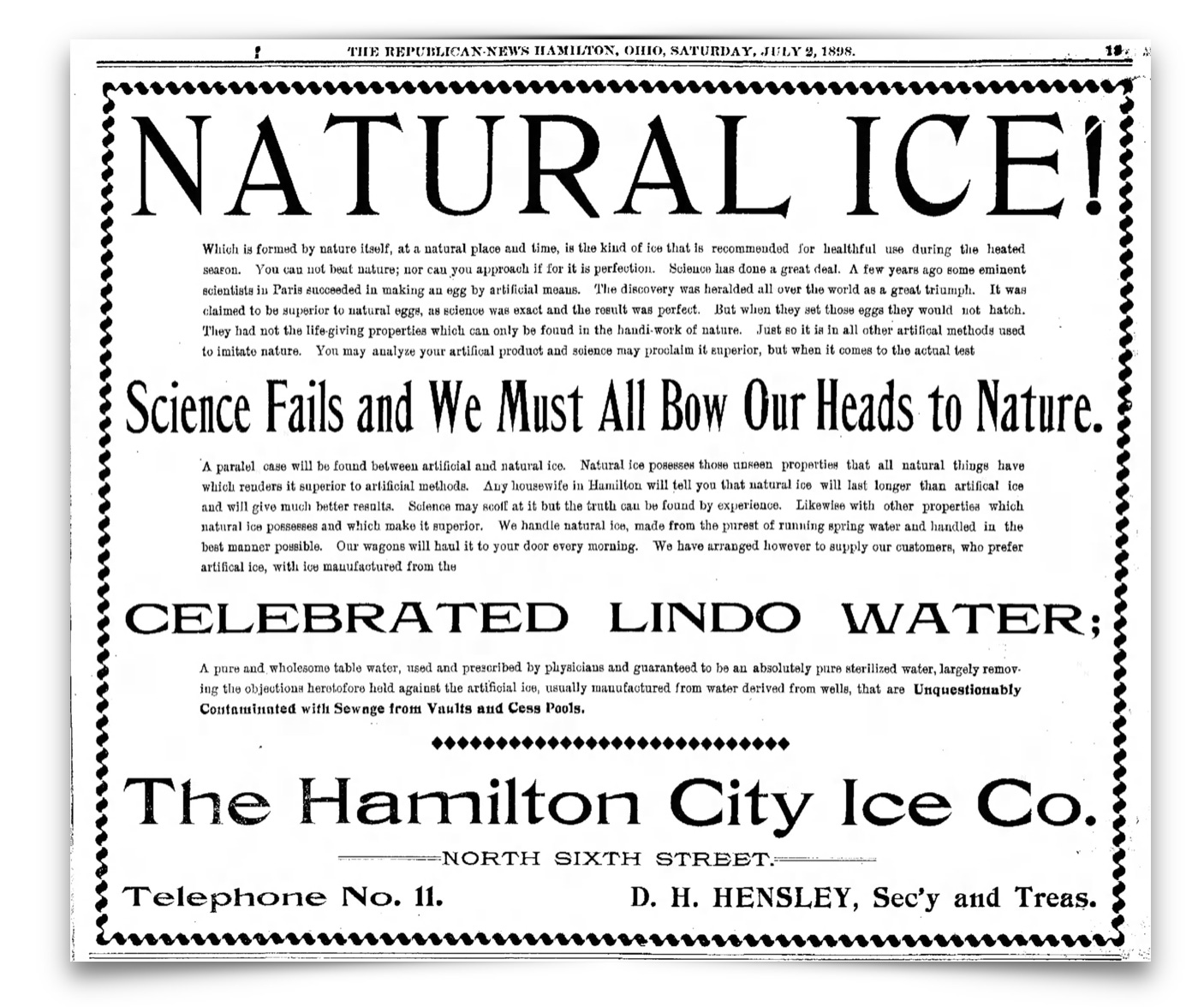

As the ice manufacturing industry grew, the incumbent ice industry would market its products as “natural ice,” insisting a purer product — an unconvincing pitch to a public increasingly wary of pollution in bodies of water.

One 1898 advert would pronounce: “Science Fails and We Must All Bow Our Head to Nature”

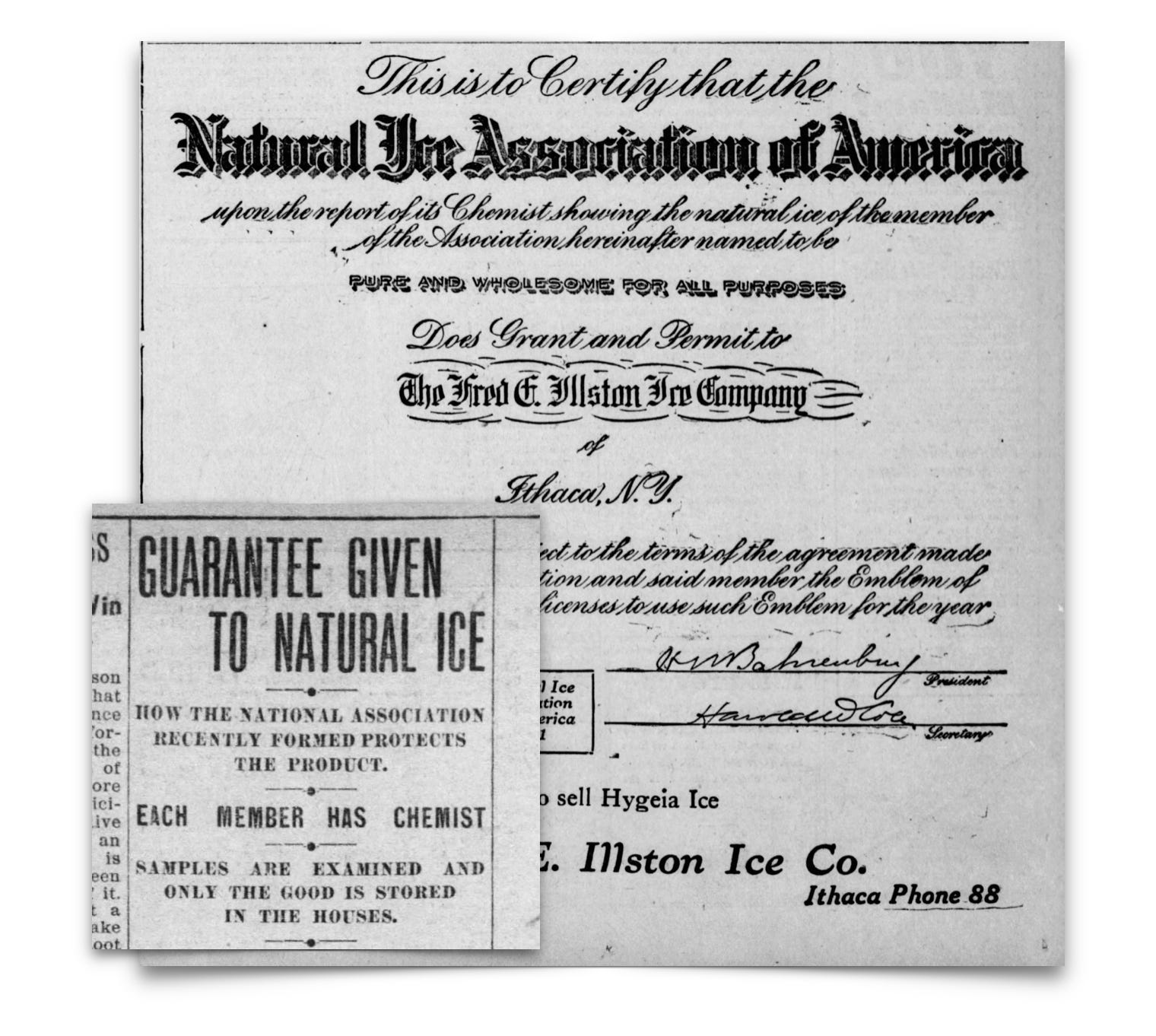

In 1911, the Natural Ice Association of America would form and offer “certification” to natural ice sellers, akin to the “organic” and “GMO-free” labels of modern times.

The effort didn’t work. As Virginia Postrel pointed out, “artificial” didn’t have the same negative connotations in the early 19th century as it does today. By the 1930s, natural ice use was in decline, but that didn’t stop ice companies from insisting that natural ice was better, such as in the 1931 advertorial on the right below that misleading claimed experts said natural ice was better.

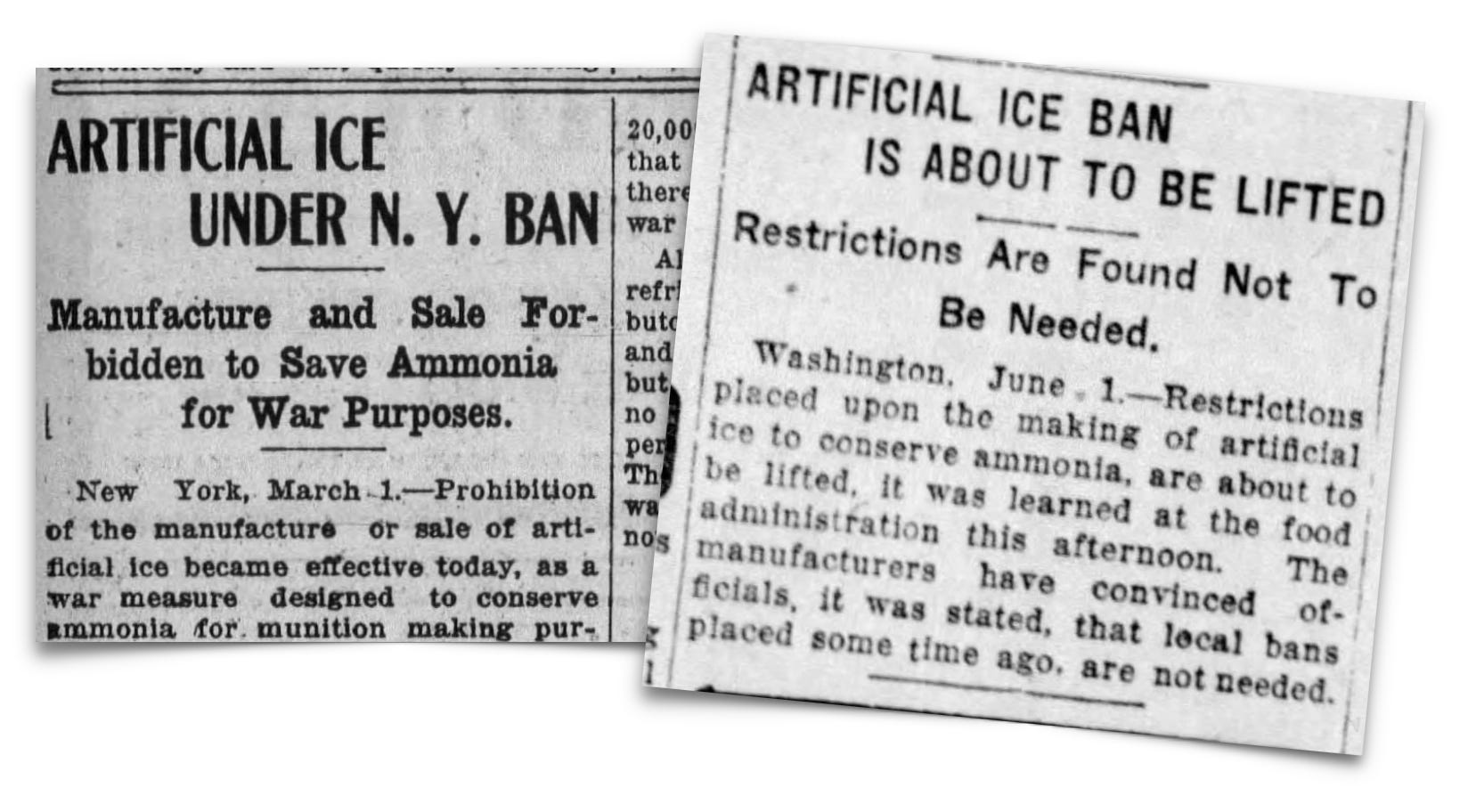

The only prohibition of artificial ice were 1918 bans limiting its production during World War 1 in the name of preserving ammonia supplies, which were a key part of the ice manufacturing process. These laws, however, appeared to be preemptive and unnecessary.

All this begs the question whether similar efforts against lab-grown meat might be more successful. So far, this seems to be the case. Had the natural ice industry preemptively lobbied to permanently outlaw the production and sale of artificial ice, it could well have hastened its arrival to consumers, if not prevented the industry from ever emerging at all.

Dr. Gorrie would never get to see his innovation change the world in the profound ways it has, but his legacy is honored with a statue in Washington DC, ironically gifted by the State of Florida, which pioneered artificial ice in the past and leads the prohibition of artificial meat today.

Note: Artificial ice caused some other controversies. Ice manufacturing plants were liable to explode. Some distrusted that food frozen for long periods of time was still edible, leading some states to pass laws about storage. The late Calestous Juma has a great chapter about this in his book “Innovation and Its Enemies.” We plan to write on this more in the future.

This article was originally published on Pessimists Archive. It is reprinted with permission of the author.