This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

To avoid the worst predicted effects of climate change, climate experts say we need to not only reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, but also remove and sequester carbon that’s already been released in the atmosphere.

There are more or less natural ways to do this — we can plant more trees (maybe even genetically engineered ones), tweak farm soil to suck up more carbon, or spread green sand on beaches. Or we can pull carbon from the atmosphere using huge machines, known as direct air capture (DAC) technologies.

Direct air capture: While the specifics vary, DAC systems typically use fans to pull in air from the atmosphere. The carbon in it then reacts with and binds to a chemical in the system. Heat can then be applied to the chemical to release the carbon for storage or reuse, and the rest of the material is returned to capture more CO2.

Unlike forests, farms, or beaches, CO2 removal facilities aren’t beholden to geographical constraints — the amount of carbon in the air is very similar across the planet, so we can establish them virtually anywhere.

And while a wildfire or logging operation can release a forest’s stored carbon, DAC gives us the opportunity to store concentrated CO2 someplace more permanent, such as deep underground or in products like concrete.

The challenge: Despite these benefits, direct CO2 removal still hasn’t really taken off — as of 2020, the world’s 15 operational DAC facilities were pulling a total of about 9,000 tonnes of CO2 from the air annually, which is about as much as 2,000 cars generate per year.

“We’re going to need to remove 10 gigatonnes of CO2 per year by 2050.”

Jane Zelikova

To have a serious impact on our climate situation, we’re going to need to capture a lot more carbon than that.

“Current models suggest we’re going to need to remove 10 gigatonnes of CO2 per year by 2050, and by the end of the century, that number needs to double to 20 gigatonnes per year,” Jane Zelikova, a climate scientist at the University of Wyoming, told BBC News in 2021.

“[Right now], we’re removing virtually none,” she continued. “We’re having to scale from zero.”

The startup: A major reason for this slow progress is that carbon accounts for just .04% of our air. That low concentration makes extracting it from the open air an expensive engineering challenge — removal costs between $100 and $1,000 per tonne, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

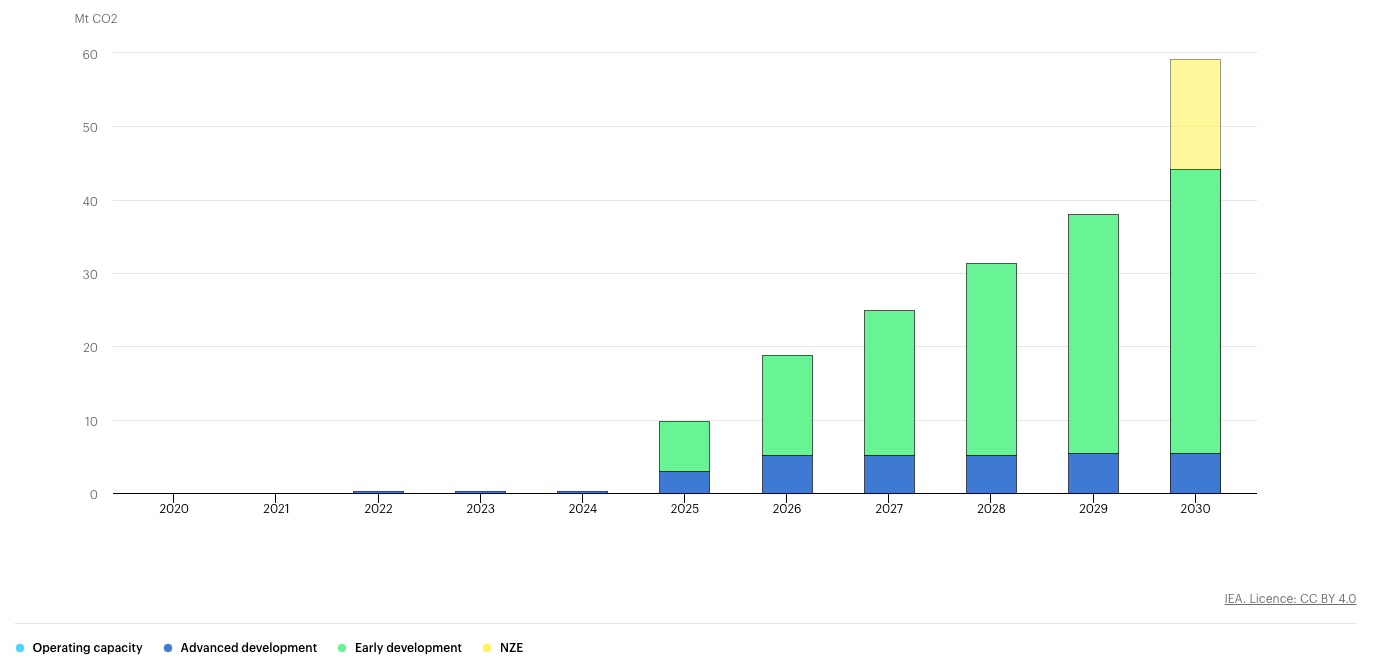

Scaling up CO2 removal tech could lower costs, making investments in DAC more attractive to governments or corporations looking to offset their emissions — and Swiss startup Climeworks is leading the way on that front.

In September 2021, it opened Orca, the world’s largest CO2 removal plant, in Iceland. On its own, that facility can remove 4,000 tonnes of CO2 per year — nearly half of what all other plants are pulling combined.

An independent third-party auditor recently confirmed that Climeworks had removed CO2 from the air at that plant and put it into the ground for permanent storage, for paying customers — something no other group has done before.

“Today’s announcement of Climeworks’ first verified deliveries is an important step for DAC, and it represents the culmination of years of investment from the Climeworks team,” said Zeke Hausfather, climate research lead at fintech company Stripe, one of Climeworks’ customers.

Climeworks’ goal is to reach multi-megatonne capacity by 2030 and gigatonne capacity by 2050, and while Orca is still far short of that, the startup has already broken ground on an even bigger CO2 removal plant in Iceland.

This one, Mammoth, will be capable of pulling 36,000 tonnes of carbon from the air annually once fully operational. Construction is expected to take 18-24 months, and once up and running, the plant will be powered 100% by renewable energy, just like Orca.

“Nobody has ever built what we are building in DAC, and we are both humble and realistic that the most certain way to be successful is to run the technology in the real world as fast as possible,” said Christoph Gebald, Climeworks co-founder and co-CEO.

In late 2021, Congress authorized $3.5 billion in funding to build four DAC hubs across the US.

The big picture: Climeworks might be leading the charge at scaling up direct carbon capture tech, but we could soon enter an era when the record for largest plant is broken again and again.

Canadian startup Carbon Engineering and US oil company Occidental Petroleum are building a DAC plant in Texas that’s expected to be operational by 2024 — initially, it will be capable of capturing 500,000 tonnes of CO2 annually, but it could be scaled up to 1 million tonnes.

The US is expected to get several more CO2 removal plants soon, too.

In late 2021, Congress authorized $3.5 billion in funding to build four DAC hubs — it’s currently seeking proposals for plants capable of capturing and storing at least 1 million tonnes of CO2 annually.

One of the companies that has announced plans to bid on the project, California’s CarbonCapture, is already building another DAC plant in Wyoming that’s expected to become operational in 2023.

Initially, that plant will be capable of capturing 12,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, but the company says that it plans to continually add modules that will increase its capacity to 5 million tonnes annually by 2030.

Again, that’s still far short of the 10 gigatonnes of CO2 experts say we need to be removing every year by 2050, but if the tech continues to scale — and governments and corporations continue to invest — getting there wouldn’t be impossible.

“I think if the world sets its mind to it, we can produce many of these plants,” Carbon Engineering’s CEO Steve Oldham told Yale Environment 360. “And we’ve done this in the past. Look at the way we scrambled for COVID vaccines. Or look at the way we scrambled for wars and got into the mass production of planes.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].