This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

It’s 2026, and you just had your first child through IVF. You would’ve tried it sooner, but the cost was too daunting, especially considering the chances that the procedure might not work. Then you discovered a new startup using AI to make IVF more successful and affordable to more people.

Overcoming infertility

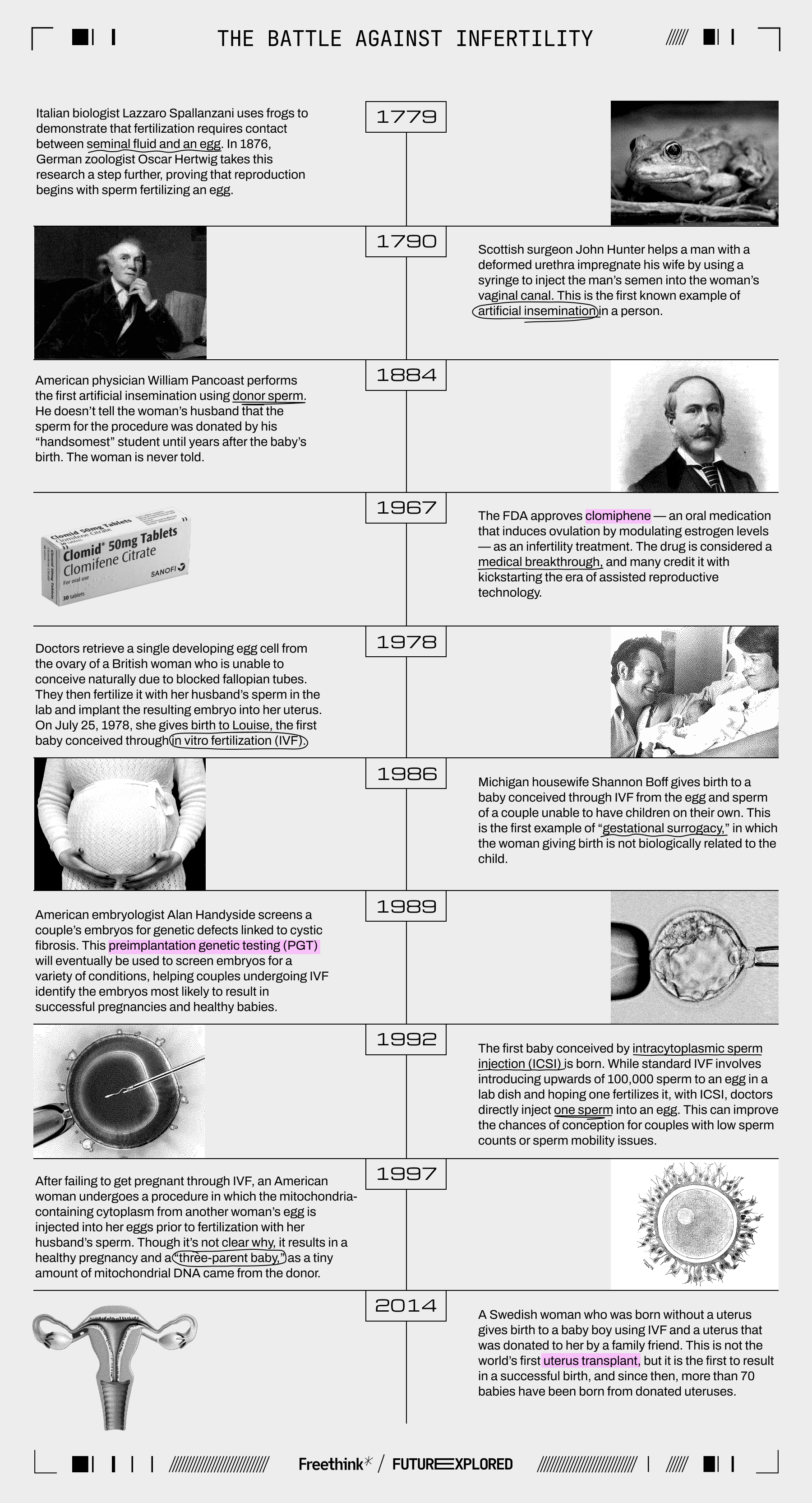

Anthropologists suspect that humans figured out that sex and childbirth were connected by 50,000 years ago (at least), but we didn’t start to really understand the biology behind reproduction until the 18th century.

That meant that for most of human history, we had no true idea about why sex sometimes didn’t lead to childbirth or what, if anything, could be done to encourage pregnancy when having sex wasn’t getting the job done.

Once we figured it out, though, we could start replacing our previous infertility “treatments,” which were largely based on superstition and cultural myths, with assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) that actually worked.

In this week’s Future Explored, let’s take a look back at the history of infertility treatments, the startup working to make them more accessible, and the in-development treatments that could change everything we know about reproduction.

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

An estimated one in six adults will experience infertility at some point in their lives, meaning that after a year of trying to conceive, they still won’t be able to get pregnant.

While an estimated 85-90% of infertility cases are now treatable, treatment does not work for everyone, and it isn’t accessible to many people who could benefit from it, often for financial reasons.

IVF is particularly expensive — a single cycle can cost anywhere from $15,000 to more than $30,000 in the US, and many couples require more than one cycle for a successful pregnancy.

IVF typically isn’t covered by health insurance, either, so many people battling infertility have to forgo their dream of having a baby because they simply can’t afford it. Others empty their savings accounts or take out high-interest loans for IVF. If it doesn’t work, they can end up childless with piles of debt.

“[Our members] pay for outcomes — if they don’t have a child, they don’t pay for their treatment.”

Nader AlSalim

Nader AlSalim, CEO and co-founder of the startup Gaia, knows about all this firsthand.

“My wife and I invested thousands of dollars [on IVF], not knowing just how much risk was involved, nor how much we would ultimately spend,” he told Freethink. “After years of treatment across multiple clinics and countries, we were blessed with our son — but at a cost of over $50,000.”

AlSalim’s frustration with his own experience drove him to hunt for a solution that would make IVF more accessible to more people. That led to Gaia, an Atomico-backed startup that takes some of the financial risk out of IVF.

“Our members know exactly what they’ll pay and when,” AlSalim told Freethink. “They pay for outcomes — if they don’t have a child, they don’t pay for their treatment.”

Gaia’s process starts with an advanced machine learning model, trained on data from the CDC, the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, that predicts a person’s likelihood of a successful pregnancy through IVF.

“We have enhanced our model with data from over 20,000 applicants, outcomes data from partner clinics across four continents, and detailed medication datasets, including dosage granularity,” said AlSalim.

“The millions of clinically validated data points include a vast range of variables — medical history, demographics, lifestyle factors, and treatment outcomes — allowing our model to accurately predict the likelihood of a successful pregnancy over three IVF cycles,” he continued.

“We’re giving hopeful parents the opportunity to build their families without resorting to high-interest loans or other financial burdens.”

Nader AlSalim

Gaia uses this information to determine what a member will pay upfront as a “protection fee” before each IVF cycle and their fixed, all-inclusive per-cycle cost of IVF at one of Gaia’s partner clinics — these average $7,600 and $22,700, respectively, per cycle.

If the member agrees to these costs, they pay Gaia the fee, Gaia pays the clinic for the first IVF cycle, and treatment can begin. If they don’t have a baby, they can pay another protection fee and Gaia will pay for another IVF cycle.

If the member has a baby within three cycles, they pay Gaia back for the full cost of however many IVF cycles it took. This repayment can be all at once or over eight years in monthly installments with interest.

If they don’t have a baby after completing one or two cycles and decide to stop trying, they only have to pay Gaia back for part of the cycle costs. If they don’t have a baby after completing three cycles, they don’t pay anything beyond the upfront protection fees.

“This is the solution I wish existed throughout my own journey.”

Nader AlSalim

The challenge now is making Gaia available to more people. The startup currently works with many clinics in the UK, but only just made the leap across the pond to America in June 2024. Now that it has one partner clinic in the US, though, it’s eager to expand across the nation.

“By removing the financial uncertainty and astronomical upfront costs, we’re giving hopeful parents the opportunity to build their families without resorting to high-interest loans or other financial burdens,” said AlSalim.

“This is the solution I wish existed throughout my own journey,” he continued, “and the solution Gaia is proud to offer today.”

Beyond IVF

While Gaia uses AI to make financing IVF less risky for prospective parents, others are working to cut its cost through automation and advanced embryo screening methods that could reduce the number of cycles needed for success.

Still others are developing brand new infertility treatments that could allow us to overcome hurdles to reproduction that even IVF can’t help — like the lack of a womb, eggs, or sperm.

Here are three of the most exciting ideas that could fundamentally change how people achieve parenthood in the future.

IVG

The idea: Some people can’t conceive due to lack of viable sperm or eggs. In vitro gametogenesis (IVG) reprograms a person’s blood or skin cells back into an embryonic-like state — these “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPSCs) can then be coaxed into becoming sperm or eggs, which could then create embryos with IVF.

This could allow couples who do not have viable eggs and/or sperm to have a baby that is biologically related to them both — and with a couple additional steps, it could potentially even allow same-sex couples to have biological children together. If this approach ends up working reliably enough, it could one day be a less invasive alternative to traditional IVF, eliminating the need for hormone injections and surgery to collect eggs.

The story so far: IVG works in rodents — scientists have made both eggs and sperm from the skin cells of female and male mice, respectively, and then used them to produce offspring.

They have also created eggs from a male mouse’s skin cells and fertilized them using sperm from another male mouse. Those IVF embryos were then implanted in a surrogate who gave birth to seemingly healthy pups that were biologically the offspring of two male mice.

In May 2024, scientists at Kyoto University in Japan announced that they had created the precursors to human eggs and sperm from iPSCs, but experts predict it’ll be at least a decade before IVG could reach infertility clinics.

What they’re saying: “Although many challenges remain and the path will certainly be long, especially when considering the ethical, legal, and social implications associated with the clinical application of human IVG, nevertheless, we have now made one significant leap forward towards the potential translation of IVG into reproductive medicine.” – Mitinori Saitou, lead researcher of the Kyoto University study

Gene therapies

The idea: An estimated half of infertility cases have a genetic cause, and gene therapies that edit DNA or add healthy copies of missing or damaged genes could one day be used to correct infertility-causing mutations in people who want to have children.

Gene therapy could also potentially be used to correct mutations in embryos that would prevent them from leading to successful pregnancies. However, gene editing embryos (or germ cells) is highly controversial for its potential to have unintended consequences or lead to the creation of “designer babies.”

The story so far: Researchers have already demonstrated several gene therapies that could one day treat infertility. In 2021, for example, Chinese scientists used CRISPR to correct a genetic mutation that causes azoospermia — a condition in which males don’t produce sperm — in mice, allowing them to sire offspring.

The following year, Kyoto University researchers made female mice infertile by breeding a mutation into a gene in their ovaries’ granulosa cells, which play an important role in reproduction. They then transported functional copies of the gene into those cells, which cured the rodents’ infertility. This approach could one day be used to treat several genetic causes of human infertility.

Researchers are also looking into gene therapies to treat the 1% of people assigned female at birth (AFAB) who have premature ovarian insufficiency, in which their ovaries stop working normally before the age of 40 — in some cases, the issues can begin when they are still teens.

What they’re saying: “I wasn’t sure they would become pregnant. I was surprised to see those babies! … The question is how risky this procedure is [for humans, but] in principle it should work.” – Takashi Shinohara, lead author of the Kyoto University study

Artificial wombs

The idea: Devices that mimic the uterine environment could be used to gestate babies for people that lack a hospitable womb of their own, such as people born without a uterus or who’ve had hysterectomies.

Artificial wombs could also potentially help people who are able to get pregnant, but unable to carry pregnancies to term. In those cases, a fetus could theoretically be transferred to the artificial womb after first developing as long as possible in a uterus.

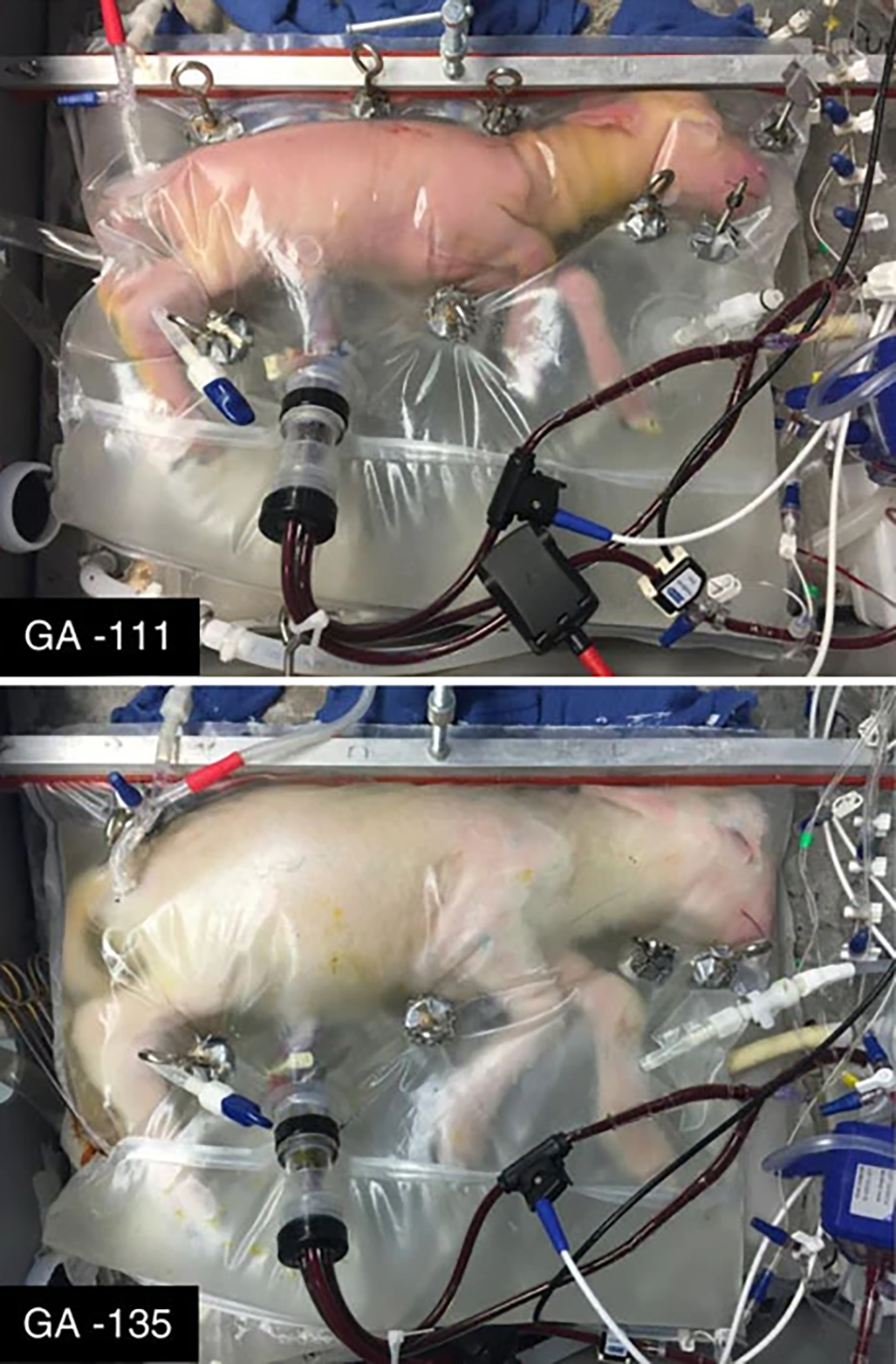

The story so far: In 2017, scientists transferred lamb fetuses from a uterus into an in-development artificial womb, known as the “Biobag.” The fetuses continued to develop in the Biobag for four weeks before being “delivered,” and while some did experience complications and others were sacrificed for study, at least one lamb lived for at least a year after its “birth.”

Since then, more than 300 lambs have been partially gestated in Biobags, and those are just one of several artificial wombs under development — a team in Toronto recently experimented with keeping pig fetuses alive in an artificial womb, though the results of that study have yet to be announced.

While the FDA is currently considering clinical trials for artificial wombs to support premature babies — like super incubators — we likely won’t see one that could support a human life from the embryo stage through birth for a long while. Scientists are still trying to figure out how to fully gestate mice in artificial wombs, and there are strict regulations on human embryo research.

What they’re saying: “[T]he next logical extension of this technology . . . is that it expands to improve infertility and decrease maternal complications of pregnancy.” – Laura Johnson Dahlke, author of “Outer Origin: A Discourse on Ectogenesis and the Value of Human Experience”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].