This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

An impact from a massive asteroid ended the age of the dinosaurs, and it’s all but certain that an equally large asteroid or comet will head Earth’s way again at some point in the future — but unlike the dinos, we may be able to stop a threatening space rock from taking us out.

The birth of planetary defense

In 1993, scientists determined that Shoemaker-Levy 9 (SL9), a comet recently discovered orbiting Jupiter, was likely to collide with the gas giant the following year. This was huge news, as astronomers had never gotten a chance to witness such an impact event before.

For six days in July 1994, they trained their telescopes on Jupiter and watched as pieces of SL9 slammed into the planet, sending giant plumes of superheated material high into its atmosphere.

“Shoemaker-Levy 9 was a sort of punch in the gut.”

Heidi Hammel

The dark scars SL9 created in Jupiter’s cloud tops dissipated a few months later, but the comet’s impact on the astronomy community lives on in “planetary defense” — efforts to detect and track asteroids, comets, and other near-Earth objects (NEOs), predict possible impacts with Earth, and prevent potentially devastating collisions.

“Shoemaker-Levy 9 was a sort of punch in the gut,” Heidi Hammel, who led the team using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to observe the SL9 collision, said in 2019. “It really invigorated our understanding of how important it is to monitor our local neighborhood, and to understand what the potential is for impacts on Earth in the future.”

Looking up

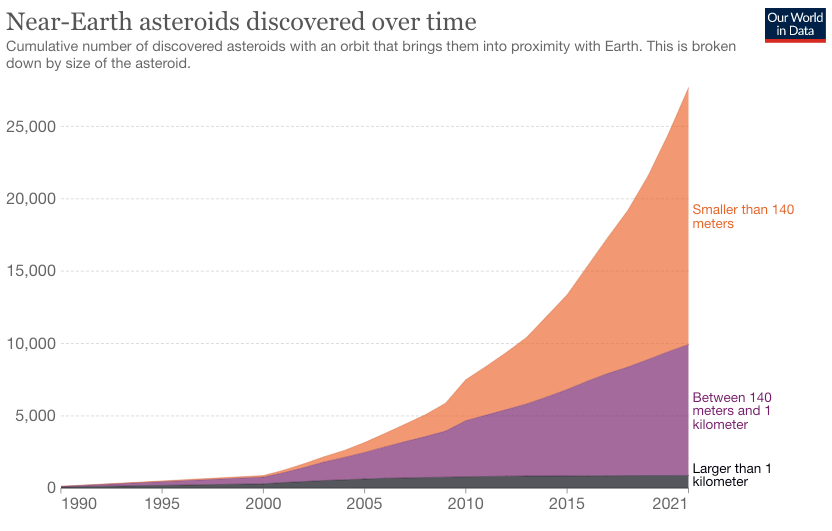

We can’t protect Earth from a threatening asteroid we don’t know exists, so in 1998, NASA established the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Observations Program to fund efforts to identify, track, and categorize NEOs.

In 2005, Congress directed the program to identify at least 90% of the predicted number of NEOs larger than 460 feet wide — the size a space rock would need to be to wipe out a city — but as of June 2021, only 40% of the estimated number of large NEOs had been identified.

This missing data could have very real consequences, too. In 2019, an asteroid estimated to be 195 to 425 feet wide flew within 40,000 miles of Earth — about one-fifth the distance to the moon — and it wasn’t spotted until the day of its flyby.

One factor holding the NEO program back is its large reliance on ground-based optical telescopes — because those can only be used to hunt for threatening asteroids at night, astronomers can’t see any approaching our planet during the day from the direction of the sun.

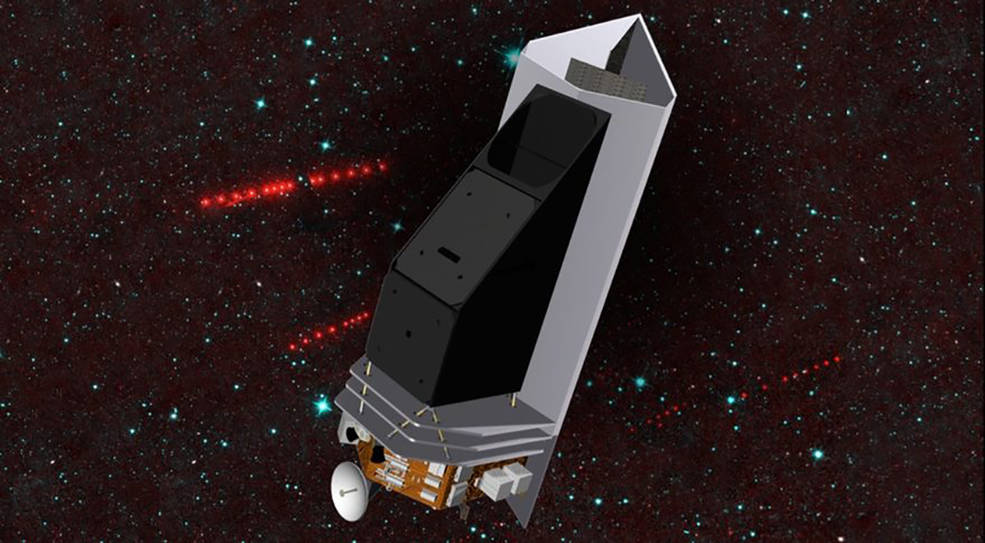

A surge of new asteroid discoveries could be just on the horizon, though, thanks to the Near-Earth Object Surveyor (NEO Surveyor) space telescope, the world’s first spacecraft specifically designed to find hazardous NEOs.

“NEO Surveyor operates at thermal infrared wavelengths and is therefore very sensitive to dark objects,” Amy Mainzer, NEO Surveyor principal investigator, told SpaceNews. “It searches the near-sun regions of the sky, thus allowing it to find objects with the most Earth-like (and therefore potentially hazardous) orbits.”

NASA hasn’t set a launch date for NEO Surveyor yet — it might launch in 2026, but funding issues could push it back to 2028. Either way, the telescope is expected to identify about 66% of city-threatening NEOs within 5 years of launch and reach the goal of 90% within 10 years.

“Although a significant impact to the Earth is of course a very rare event, we don’t know when the next one might be, and NEO Surveyor is designed to find out,” Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer, told SpaceNews.

“Software now can do things that 20, 30 years ago you would not even dream about, you would not even think about.”

Zeljko Ivezic

NEO Surveyor isn’t our only hope for detecting more asteroids, either.

In early 2022, the NASA-funded Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) was updated to include two new telescopes, bringing the total to four and making it the first system capable of surveying the entire night sky for threatening NEOs every 24 hours.

Researchers from the University of Washington and the Asteroid Institute then unveiled THOR, a computer algorithm capable of spotting new threatening asteroids in old telescope data, in May 2022 — it’s already been used to identify more than 100 previously unknown NEOs.

“[S]oftware now can do things that 20, 30 years ago you would not even dream about, you would not even think about,” THOR researcher Zeljko Ivezic told the New York Times.

Bullseye

Being able to predict a species-threatening NEO impact is a major part of planetary defense, but it’s not worth much if we can’t actually defend our planet from the space rock — we’d be just like the dinosaurs, but with the added bonus of knowing an apocalyptic event was imminent.

After years focused on finding NEOs, the “prevention” side of planetary defense recently took a huge leap forward thanks to NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), the first demonstration of tech that could possibly prevent an incoming asteroid from hitting our planet.

“It’s basically like throwing a tennis ball at a 747.”

Elena Adams

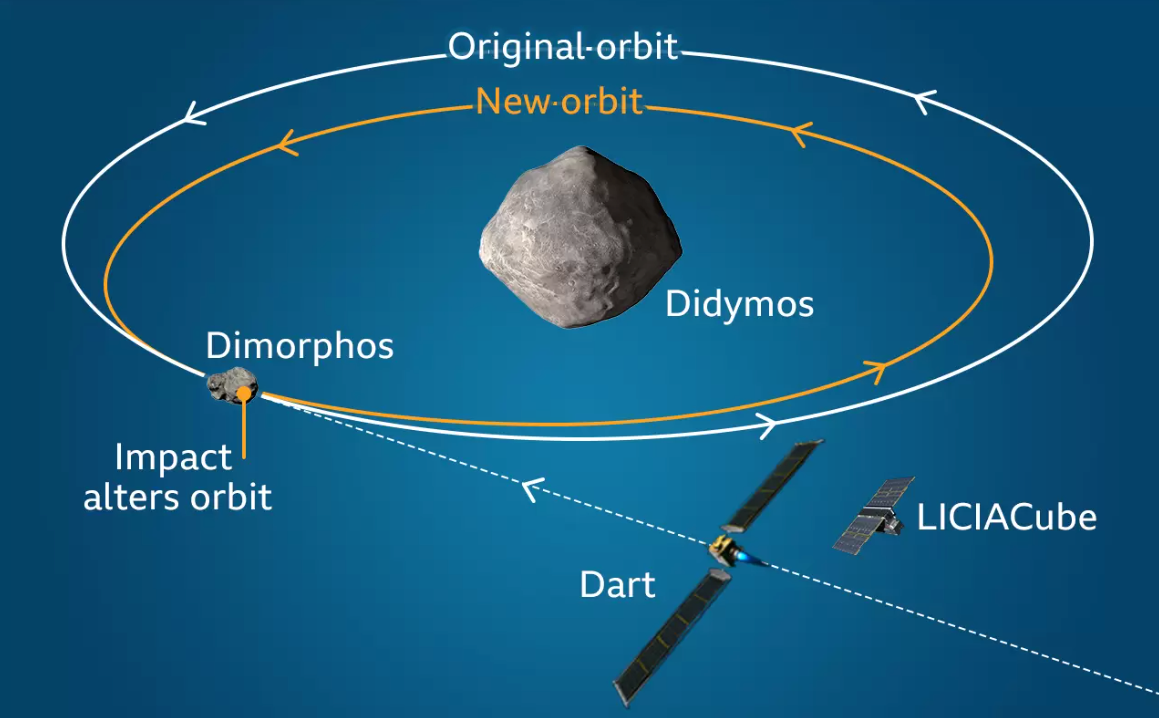

The goal of the DART mission was to slam a refrigerator-sized spacecraft into Dimorphos, a 530-foot asteroid orbiting the much larger asteroid Didymos, in the hope of shifting its orbit.

The asteroids are millions of miles away from Earth — too far to be a collision threat, but perfectly situated for studying the effect of smashing a spacecraft into a space rock.

“It’s basically like throwing a tennis ball at a 747,” Elena Adams, the DART mission systems engineer at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), told CBS News. “If it goes fast enough, you’re gonna move it.”

“[DART is] a first test of, can we actually do it?” she continued.

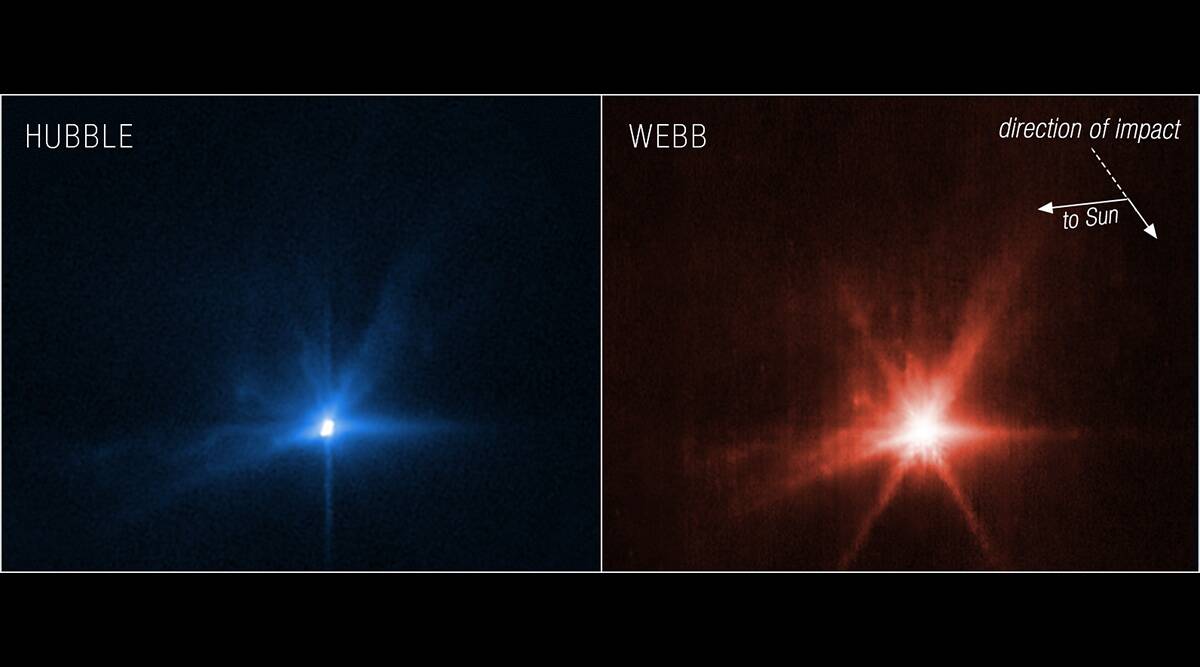

NASA passed that test on September 26, 2022, when DART successfully hit its target 10 months after launch.

Scientists are now studying observations of the collision collected by space telescopes, DART’s own imaging instrument (before it was smashed), and a small satellite released by DART just 15 days prior to its impact, called LICIACube, developed by the Italian Space Agency.

This data should help determine whether the impact did nudge Dimorphos and cause its orbit around the larger asteroid to shorten by about 1%, as NASA hoped it would.

While that change might not seem like much, even a slight push, if given early enough, could direct an asteroid off a collision course, meaning DART’s ability to move Dimorphos would put us a major step closer to being able to protect Earth from a threatening NEO.

“NASA works for the benefit of humanity, so for us it’s the ultimate fulfillment of our mission to do something like this — a technology demonstration that, who knows, some day could save our home,” said NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy.

DART might have been the first demonstration of planetary defense tech, but it likely won’t be the last — the China National Space Administration plans to launch its own asteroid deflection test in 2026.

In the more distant future, we could see tests of other ways for preventing an impact — planetary defense researchers are exploring the viability of systems designed to dice NEOs into non-threatening bits, and (yes, really) using nuclear bombs to simply blow them up.

The bottom line

Thanks to these and other planetary defense efforts, we’re now better prepared than ever before to prevent a potentially devastating impact.

That still doesn’t mean we’d actually be able to stop a collision, though — in 2021, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office failed to prevent an asteroid impact in a simulation exercise.

That hypothetical asteroid was expected to hit Earth just six months after its discovery, and NASA thinks it’d need 5 to 10 years notice to effectively divert a threatening space rock — further emphasizing the need to discover as many dangerous asteroids as possible, as soon as possible.

“Our goal is to find any possible impact years to decades in advance so it can be deflected with a capability using technology we already have, like DART,” said Johnson. “DART, NEO Surveyor, and ATLAS are all important components of NASA’s work to prepare Earth should we ever be faced with an asteroid impact threat.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].